|

It’s a good idea to have backup funds—cash that you can get to relatively quickly for emergencies. If you keep cash in checking or savings accounts, or even high-yield savings accounts, the interest you’re earning is rising at the moment, but it’s not equal to inflation. Even CDs with long terms are losing out against inflation. T-bills are, too, but not by as much right now. Treasury bills, or T-bills, are a short-term government debt obligation backed by the U.S. Treasury. These bills can be purchased for a small investment—from a minimum of $100. You need no broker; you can buy T-bills from the government at TreasuryDirect.gov. You purchase a T-bill at price that is discounted from its maturity value. For example, you might buy a $1,000 T-bill for $970. When the bill reaches maturity, you would receive the full face value of $1000, a gain of 3%. That’s treated as interest for tax purposes, but only at the federal level. T-bill interest is exempt from taxation at the state and local levels. You can also buy T-bills from banks and other institutions, but you’ll likely pay a commission or transaction fee. That comes out of the maturity value, which means lower earnings for you. T-bills have varying maturity dates: 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 13 weeks, 17 weeks, 26 weeks, and 52 weeks. (Not all of these options are available at a given “auction” date.) As you can see, these short spans mean a lot of flexibility compared to a CD, for example. The interest does not land in your account until you sell at the maturity date. It is not accruing or compounding. You should not sell a T-bill until maturity; if you do, you could take a loss on the investment—not only losing interest, but possibly some principal as well. At the moment, T-bills can be a good place to park some of your cash and earn a little bit more. The reason is that when inflation is rising, the price of T-bills rises too, and a little bit faster than the bank offerings do. Here are some examples of recent interest rates:

TreasuryDirect.gov has a lot of information about not only T-bills, but also government notes and bonds. Notes are medium-term investments, and bonds are long-term investments. For cash that you might need sooner rather than later, T-bills are best. People are flocking to bills, notes, and bonds at present, so the TreasuryDirect.gov website has been overloaded. It’s best to try during non-business hours. For Further Exploration

“Erin Talks Money” is a YouTube channel with a focus on finance. This video deals specifically with T-bills. Erin is not a certified financial adviser, but her information is fairly well researched.

0 Comments

Early in the 2000s, I was a few years out of grad school, with a master’s in environmental studies. I worked full time as a freelance editor and had a sideline as a tax preparer. But my partner and I had moved from Massachusetts to Florida, which was a major life change. Instead of my income going up, which had been the plan, it had stalled at a relatively low level. I had been a jack of all trades most of my life—I couldn’t seem to settle on a single focus, and I often changed course after a while. I had done leather craft, been a lab technician, taught guitar, worked as a secretary, a temp worker, tax preparer, and yes, an editor. I had gone to grad school to enhance my marketability as an editor of life sciences textbooks. But now, with my income having dropped, I was thinking about yet another career change. Maybe what I really wanted to be when I grew up was a forest ranger or park ranger, or at least a biologist working for an environmental agency. Did I really want to start over again once more, or was I just desperate and wanting a way out? Was I searching—or avoiding? The fact is, I was already grown up. I wasn’t equipped to start job-searching for an entry-level position in a new field—especially one that didn’t pay well. And I was no longer as physically strong as I used to be, which probably meant working as a ranger was off the table. The time for making a change like this had passed, but I hadn’t quite realized it.

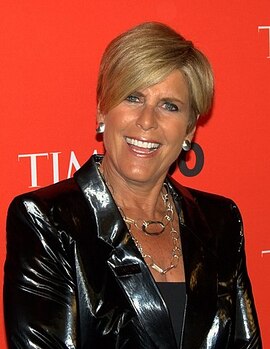

Suze listened to her story, and when the woman was done, Suze asked her, “My dear, why are you not making twice as much?” This simple statement—no deep philosophy, no statistics, no advice—went off in my brain like a blinding flash. Today we would use the mind-blown emoji. It’s hard to describe the shift that I felt, but many changes followed. They fit generally under the phrases Get Real and Get Serious. My longest history of gainful employment had been as an editor, and I was very skilled and successful in this field. Acknowledging this allowed me to drop all the alternative jobs that popped up in my restless mind and to stop trying to re-invent myself. In other words, to get real. A freelance editor needs to actively look for editorial work. I had become too relaxed about scouting for new contacts, making connections, and staying in touch. This part of freelance life was not my favorite, but I knew it was necessary. I had to get serious. I did take action. I went to our local library reference department and pulled out a hard copy of Literary Market Place to begin searching for publishing companies. I spent time working through this resource and writing down potential contacts—and I made some serendipitous connections. It “just so happened” that when I contacted McGraw-Hill, they were looking for a developmental editor in life sciences. I also did work later on for W. W. Norton, Pearson Addison-Wesley, and other, smaller companies, all of which I sought out and followed up on. The following year, my income doubled. In fact, it almost tripled. The year after that, it doubled again. I’d like to say that my income stayed at that high level until I retired, but contract work is unpredictable, and the market began to change. Still, I wouldn’t have been as financially successful had I not heard that wake-up call from Suze Orman.

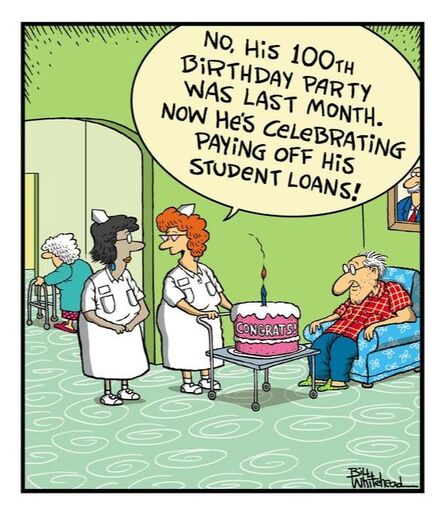

I said earlier that it was hard to describe the shift I felt, but I’m going to give it a try. That shift wasn’t simply getting new information and using logic to plot a rational course of action, although I did take action. Instead, it was a consciousness shift. The frame of mind, or whatever it was, that had led me into this stuck place didn’t just change; it dissolved. I think that as a result, I found open doors—doors I hadn’t looked for and hadn’t been able to look for. Opportunities suddenly appeared. Skeptics might say that those opportunities were there all along, and perhaps that’s true—but for me, they might as well have not existed until I went looking for them with my “new eyes.” In an earlier post, I talked about using expense tracking to see where you’re at financially. But income and expenses are only part of the picture. Another aspect is what you own (assets) versus what you owe (liabilities). Please note that I’m using loose definitions here, and I’m only talking about personal assets. Accountants use more complex definitions, and business assets, such as income-producing rental property, are not included. Assets More specifically, assets are things you own that you could sell—for example, furnishings in your home, a car, artwork, musical instruments, your late grandma’s chess set, and so on. Your home itself is an asset if you’re buying rather than renting. Shares of mutual funds or other personal investments count as assets. Cash you have on hand or the cash value of bank accounts are also assets. Your dwelling is not an asset if you rent it. Neither is a vehicle you lease. Rental and lease payments go under expenses, although car leasing is a special case. Liabilities The mortgage you’re paying on your residence is a liability, and so is car loan debt. In these cases, the debt you owe is “secured” by the asset; if you fail to make the payments as you agreed, the assets could be subject to foreclosure or repossession. You might also have other liabilities, such as credit card debt. Credit card debt is primarily “unsecured” debt—for example, you used credit cards to purchase meals out, buy gasoline, pay for a vacation, and so on. Expenditures like these are basically personal expenses, and you’re paying them by taking out a loan from the credit card company at a huge interest rate (average is 16.15%). You promise to pay the company the original amount plus interest. There’s no asset that can be “taken back.” Student loan debt is also unsecured debt. It’s not like the Fed can take back your degree! Plus there’s no guarantee that you’ll even earn a degree. Either way, you have promised to pay. Net Worth The difference between your assets and your liabilities is termed your “net worth.” When people talk about “wealth,” they’re referring to a high net worth. How much income someone makes doesn’t figure in. Here are two hypothetical households with different net worth:

Because household A has no liabilities, A’s net worth is equal to A’s assets. Household B has sizeable liabilities, and so B’s net worth is lower, even though B has more in assets. Put another way, household A is “wealthier.” It’s possible to have liabilities that exceed your assets. Being “upside down” on a mortgage is one example. If you owe more than you own overall, you have a negative net worth. According to the financial-advice company Motley Fool, 16.6 million American households, or 14%, had a negative net worth in the spring of 2017. (I don’t imagine it’s any better now.) What do you think is the biggest contributor to this negative net worth? It’s not mortgage debt, credit card debt, or payday loans, although these do contribute. The largest liability burden in households with negative net worth is student loan debt. This isn’t a problem only for younger generations; an article from Business Insider in 2019 reported that more than 3 million Americans over age 60 collectively owed more than $86 billion in unpaid student loans. That kind of liability can kick the stuffing out of net worth. For more details:

Maurie Backman, “16.6 Million U.S. Households Have a Negative Net Worth—Here’s the Surprising Reason Why.” Motley Fool, May 14, 2017. (Click here.) Kelly McLaughlin, “3 million senior citizens in the US are still paying off their student loans.” Business Insider, May 3, 2019. (Click here.) How many times have you opened a video or article on personal finance and seen this? “STEP 1: Set Your Budget Goals” Oh, gag me with a spreadsheet! If setting nice, simple, left-brain goals could solve our problems, we wouldn’t have many. Here are some of my own strategies to improve personal finance without reliance on a set budget. Strategy 1: Carry cash. Say, $300 to $600 a month—you can figure out your own amount. Use this cash to pay for your smaller purchases, like lunch out, drugstore shopping, coffee, haircuts, and so on. One reason to pay cash is that you see and experience the exchange of your money for goods; the money in your wallet dwindles. With card purchases, it’s like magic! They hand you back your card! Nothing really happened! Strategy 2: Use only debit cards as much as possible. Leave the credit cards shut in a secure drawer. The advantage is pretty obvious: you don’t increase your debt. To use this strategy successfully, you’ll need to keep an eye on your account balances. Which you do anyway, right? Right?? Strategy 3: If you must use a credit card, be prepared to pay the balance off before the interest-free “grace period” is up. Strategy 4: If you have a large purchase that you must put on a credit card, and it’s too much to pay off in one lump, pay the largest amount you can and don’t use that card again until it’s down to a zero balance. A sub-strategy to this is to try to keep at least one card at zero balance at all times. Strategy 5: Always pay more than the minimum balance on any debt. If you have a mortgage, try to pay more toward principal each month (find out from your lender how to do this). The less debt you carry, the better. Strategy 6: Use expense tracking. Budgeting and expense tracking may seem like the same thing, but they are not. With a budget, you set monthly goals for what you’ll spend in different categories, like food, gasoline, electricity, and so on. Then you get to play the game of going over your budget or staying under, and this may lead you to throw up your hands! Expense tracking lets you see what you are currently spending in different categories, compared to income. Your bank may have online tools or apps that track income and expenses for you with a few clicks. By looking back over three to six months, you can see how your average expenses run. This practice helps you by revealing what’s going on in your financial life. Remember how I said that with card purchases, it’s like nothing really happened? This is one way to find out what’s happening. Which you want to know. Seriously. Strategy 7: Avoid categories like “Miscellaneous” or “Uncategorized.” Always assign expenses to a descriptive category. For example, items you buy at a drugstore, whether with cash or via debit or credit, could go under “Health care,” “Personal care,” or “General merchandise”—it doesn’t really matter as long as it’s not vague.

Strategy 8: Along the same line, avoid categories like “Credit card payments” or “Finances.” As with number 7, you want to use a descriptive category. Was that card purchase a car repair? It should go under “Automotive.” Most online tools don’t help you track how much interest you’re paying on outstanding debts. That’s kind of a different issue from expenses. In a later post, I’ll talk about assets and liabilities. What financial strategies do you employ? Are there any you would add? Which ones do you disagree with? These tongue-in-cheek tips have been compiled from my 20 years of experience serving clients as a professional tax practitioner. I’m assuming that no huge inheritance is waiting in the wings. If it is, you may have to work harder to go broke.

|

Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed