|

Stars begin as enormous fusion reactors. At first, hydrogen atoms fuse to become helium atoms—with a tiny bit of matter being converted to energy in the process. That tiny bit produces lots and lots of energy; it’s like a huge, continuous hydrogen bomb explosion. Toward the end of a star’s life, it’s rich in complex elements formed by additional fusion reactions. One of these elements is carbon. Carbon is the champion of living things. Without carbon, there would be no life on Earth.

In this way, carbon and other heavy elements landed in our solar system. We truly are stardust.

Diamonds are pure carbon in a transparent, crystalline structure that gives it both hardness and resistance to heat. A diamond melts at 4,000°C (7,232°F), and is the hardest naturally occurring substance on Earth. Graphite is also pure carbon, but in a different crystal lattice arranged in layers. Graphite has about the same melting point as diamond, but it’s soft and slippery because its layers can slide under physical pressure; for this reason, graphite is useful in lubrication and as pencil “lead.” Within your body, carbon is vitally important to proteins that form your skin, bones, muscles, brain, and other organs, and it is found in small molecules, hormones, and large-stranded DNA. Carbohydrates are energy-rich molecules which, as the name tells you, consist of carbon combined with water (H2O). Fats consist of long chains of carbon atoms with hydrogen atoms attached; the bonds between the carbons store energy. Every tissue, structure, and process in Earth’s living organisms depends on carbon. The chemistry of carbon is called organic chemistry for this reason. Carbon doesn’t last forever, but for our purposes, it’s close. All the carbon that arrived as the Earth was forming so long ago is pretty much still here. It cycles through both the living and inanimate worlds; plants ultimately build their bodies from the carbon in carbon dioxide, and animals from eating other organisms. We are all exchanging carbon all the time. Some of the carbon atoms in your body may have cycled from an ancient ocean or forest, or from long-dead creatures as yet unknown. Some of the carbon you take in may have resided most recently in your ancestors, friends, or even your pets—whether carried in the air you breathe or having been incorporated into the food you ate for lunch. Whatever the case, may carbon be with you. It unites us all. This article is dedicated to my long-time friend Deborah Robbins.

6 Comments

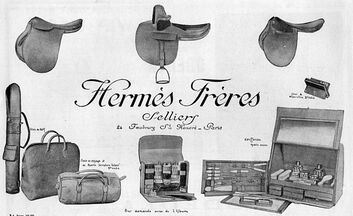

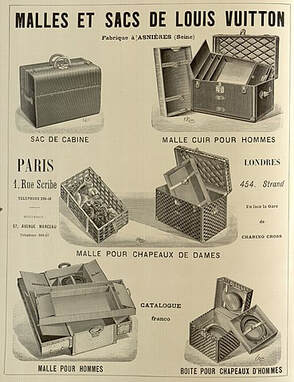

I was working as a guitar teacher at the San Francisco School of Folk Music and nearing burnout. I wanted to reinvent myself again. I had done leathercraft as a sort of side gig to guitar teaching when I lived in Salt Lake about five years earlier, and when I saw the help-wanted ad for someone to work on handbag repair, I thought I would give it a go. Brian and Karen, the Oliviers, hired me. Brian served as the front man—he was British with an accent, tall, nicely built, with wavy dark blond hair and the rugged good looks of a prizefighter. In fact, he had been a boxer at one time—a regimental champion while in the Royal Air Force. He also dressed up very nicely. Karen, however, was the master of repair. She had a German accent and was meticulous about detail. She possessed all the skills, and except for the metalwork, which Mr. Olivier handled, her talent made the shop successful. They insisted that employees call them “Mr. and Mrs. Olivier.”

The entrance to the suite had a bell, and when it rang, Mr. Olivier would often say, “Here comes another punter,” as he pulled on his jacket and straightened his tie.

I took it to the back room and put on the welding helmet and gloves. As I began to weld a new connector onto the back, the whole butterfly dissolved into a pool of silver liquid on the bench. The piece had been cast in pot metal (a low-quality metal), and then plated with brass. Mr. Olivier told me that one could sometimes use a file on an invisible area of a metal piece to see whether it’s plated instead of solid. I did find a solid-brass piece, not a butterfly, that would work as a replacement. The owner understood what had happened, but I think she missed the butterfly. One day Mr. and Mrs. Olivier were out, and as “senior staff” I was on the front desk if customers came in. A woman entered dressed all in Gucci, carrying a Yorkshire terrier under her arm. She had come to pick up her cleaned handbag. Oddly, Yorkshire terriers like me; they are not usually friendly to unfamiliar people. She set the dog on the counter, and it proceeded to start licking my hand. Lick . . . lick . . . lick . . . I retrieved the woman’s bag from underneath the counter and slowly unwrapped it.

“Obviously, some error has been made,” I offered, wrapping the bag back up. This was a Major Problem. “I will need to talk to Mr. Olivier about it. I’m very sorry, but we will see what can be done.” She picked up the Yorkshire terrier, which gazed wistfully at me, and stormed out, leaving a trail of angry disappointment behind. When we cleaned bags, we used solvents to remove dirt, oils, and any old wax from the surface. A relatively mild solvent, such as water or diluted alcohol, would usually take care of this. But for some jobs, such as stripping, we used acetone.

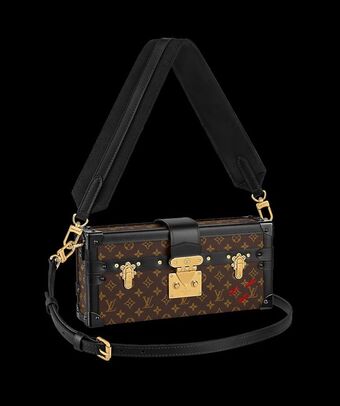

We also did repair and polishing work on brand-new bags from the stores in that area. Sometimes the bags would be damaged while on the rack. This was when I came across my first Louis Vuitton bag with a price tag of $750. That was six times what I made in a week! Prices seem to have stayed as high or higher in today’s dollars, as you can see from the images I’ve included. When I left the job at Olivier’s, Mr. and Mrs. Olivier were not getting along well. Mrs. Olivier wanted out of the business. I didn’t stay in touch with them; I got an office job in South San Francisco working for a musical instrument importer and wholesaler.

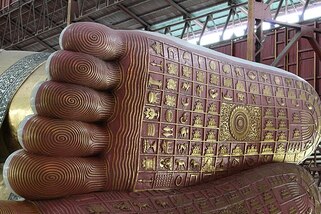

During what would be his final journey, Gautama Buddha first became ill when he and some of his disciples were staying at Beluva for the rainy season. His pain was very great, but through meditation he was able to endure it, and he made a recovery.

Masters commonly hid the inner secrets of their craft or teachings from their followers. This was termed “the master’s fist.” Gautama Buddha said that in his teachings there was no “master’s fist.” The Buddha believed that these teachings belonged to all people, without regard to caste or other distinctions. Gautama went on to say, “Ānanda, . . . I am old and wasting away with age. I have traversed life’s journey and reached the end of my time. I am already eighty. As an old cart will move only if strapped up, my body is kept going by being strapped up. It is only when . . . [I enter] into the concentration of mind that has no outward characteristics that [my] body is sound.

The word translated as “island” is dīpa. Opinions vary on the translation of this word, which can also have the meaning of “lamp” or “light.” Most evidence indicates that “island” is the intended meaning, based on how those in India depended on islands or sandbars for safety during the floods of the rainy season. Jain writings also contain dīpa in this usage. But an argument can be made for the meaning of a light or lamp, which could be used as a guide; the interpretation would then be “You should be guides unto yourselves.” Shinran, founder of the Jōdo Shin sect of Buddhism, used the word “beacon”; this word suggests a light or lighthouse marking an island, combining the two meanings in a pleasing way.

For Further Exploration:

Quotations of the Buddha are taken from Hajime Nakamura’s work Gotama Buddha: A Biography Based on the Most Reliable Texts, Vol. 2 (Tokyo: Kosei Publishing Co., 2005). The story of Buddha’s decline and death is recorded in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta (Pali version). Many translations exist, but one that is worth checking out is Last Days of the Buddha by Sister Vajira and Francis Story (Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society, 2000). Buddhist scholar Thānissaro Bhikkhu has also translated this sutra. The complete text is available online here. Mary Oliver wrote a poem about the Buddha’s death, making use of some poetic license. It’s titled “The Buddha’s Last Instruction,” and you can read it here.

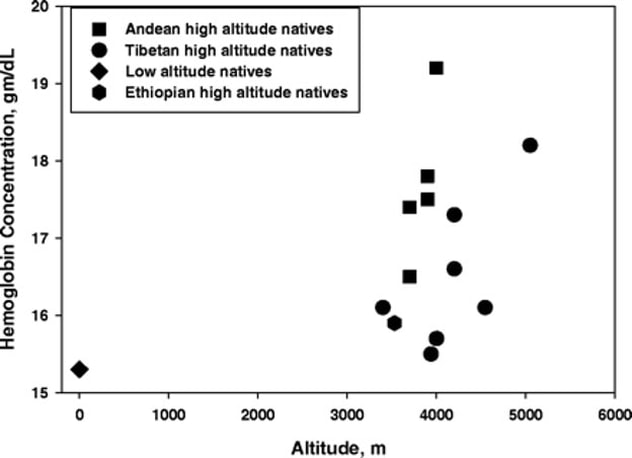

Over those thousands of years, any genetic differences that gave an individual an advantage in the high-altitude environment tended to be preserved and to increase in the population. This is the classic concept of natural selection. Tibetans are not the only people who live up high. The Aymara people of the Andes live at an average elevation of about 13,000 ft (4,000 meters). Humans moved into the Andes perhaps 11,000 years ago. And, the Amhara people of northwestern Ethiopia live at an average elevation of 10,663 ft (3,250 meters). Anthropologist Cynthia Beall of Case Western Reserve University has spent decades studying the physiology of high-altitude populations. Here are a few of the physiological differences among Tibetans, Andeans, and Ethiopians, based on her work and that of others: Tibetans:

It’s puzzling how Tibetans manage to keep their physiological oxygen high enough since they don’t show increased hemoglobin or increased oxygen in hemoglobin. Basically, Tibetans tolerate having a low oxygen level in their arterial blood, and yet their tissues manage to utilize the oxygen they need. Ethiopians are another puzzle; their hemoglobin and oxygen-in-hemoglobin measurements are close to that of lowlanders, but they too are able to thrive in the highlands. The graph below illustrates hemoglobin versus altitude. Notice that low-altitude natives are shown down in the lower left corner, and that the single point for Ethiopians is between 3000 and 4000 m altitude in the lower part of the figure. Naturally, scientists are looking for clues. In the last ten years, a gene known as EPAS1 has been studied extensively. This gene plays a role in the production of erythropoietin (EPO), which controls production of red blood cells. When oxygen is low, EPAS1 transcription is turned on and stimulates EPO production. This in turn leads to increased red blood cells and thus greater oxygen availability. You may remember the Tour de France scandals of the early 2000s that involved the use of EPO by competitors as a performance enhancing drug. When lowlanders travel to high altitude, EPO increases, and this is thought to compensate for lowered oxygen availability. In Andeans living at altitude, increased EPO is a way of life. But Tibetans and Ethiopians do not show increased EPO. Because of their elevated red blood cell count, Andean natives are at risk for developing chronic mountain sickness. This ailment is a result of increased blood viscosity, which slows circulation—particularly through the lungs. These people may suffer from low oxygen in spite of high hemoglobin. Tibetans and Ethiopians, in contrast, are more likely to avoid this condition. In Tibetans, the EPAS1 gene is altered. Although it does stimulate production of EPO, it does so at a lower level. What’s more, this particular altered EPAS1 gene is found almost exclusively in Tibetans. (A small percentage of Han Chinese also carry this altered gene.) So far, Ethiopians do not show an altered EPAS1, but they do show altered versions of some other genes in the hemoglobin and red-cell pathways. Here’s another twist to the story: the altered EPAS1 of Tibetans has evidently come from a group of hominins (closely related, archaic humans) known as the Denisovans, who went extinct about 40,000 years ago. Not much is known about Denisovans because only a few fragmentary fossils have been found. DNA analysis, however, shows that they were distinct from Neanderthals and from modern humans. Interbreeding occurred among these groups on multiple occasions over thousands of years. The altered EPAS1 has no particular effect at low altitude, which may be why it has been preserved in Tibetans and Sherpa people. Adaptation to high-altitude environments has apparently taken more than one path in humans. Scientist are continuing to investigate other possibilities to explain how Tibetans, and Sherpas in particular, are able to live the high life. For further exploration

[These first four are technical articles:] Cynthia M. Beall, “Andean, Tibetan, and Ethiopian patterns of adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia.” Integrative and Comparative Biology, 46(1), February 2006. Click here. Cynthia M. Beall, “Two routes to functional adaptation: Tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), May 15, 2007. Click here. Cynthia M. Beall, Michael J. Decker, Gary M. Brittenham, et al. “An Ethiopian pattern of human adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), December 2002. Click here. Masayuki Hanaoka, Yunden Droma, Buddha Basnyat, et al. “Genetic Variants in EPAS1 Contribute to Adaptation to High-Altitude Hypoxia in Sherpas.” PLoS ONE 7(12), December 2012. Click here. [Nontechnical:] Ann Gibbons, “Tibetans Inherited High-Altitude Gene from Ancient Human.” Science, July 2, 2014. Click here. Mark Synnott, The Third Pole. New York: Dutton, Penguin Random House LLC, 2021. [This book describes the author’s journey to Everest in search of the remains of Sandy Irvine. Along the way he tells us a lot about the George Mallory expedition, about other Everest climbers, and about the Sherpas’ abilities. It was this book that introduced me to the Denisovan EPAS1 gene.] Early in the 2000s, I was a few years out of grad school, with a master’s in environmental studies. I worked full time as a freelance editor and had a sideline as a tax preparer. But my partner and I had moved from Massachusetts to Florida, which was a major life change. Instead of my income going up, which had been the plan, it had stalled at a relatively low level. I had been a jack of all trades most of my life—I couldn’t seem to settle on a single focus, and I often changed course after a while. I had done leather craft, been a lab technician, taught guitar, worked as a secretary, a temp worker, tax preparer, and yes, an editor. I had gone to grad school to enhance my marketability as an editor of life sciences textbooks. But now, with my income having dropped, I was thinking about yet another career change. Maybe what I really wanted to be when I grew up was a forest ranger or park ranger, or at least a biologist working for an environmental agency. Did I really want to start over again once more, or was I just desperate and wanting a way out? Was I searching—or avoiding? The fact is, I was already grown up. I wasn’t equipped to start job-searching for an entry-level position in a new field—especially one that didn’t pay well. And I was no longer as physically strong as I used to be, which probably meant working as a ranger was off the table. The time for making a change like this had passed, but I hadn’t quite realized it.

Suze listened to her story, and when the woman was done, Suze asked her, “My dear, why are you not making twice as much?” This simple statement—no deep philosophy, no statistics, no advice—went off in my brain like a blinding flash. Today we would use the mind-blown emoji. It’s hard to describe the shift that I felt, but many changes followed. They fit generally under the phrases Get Real and Get Serious. My longest history of gainful employment had been as an editor, and I was very skilled and successful in this field. Acknowledging this allowed me to drop all the alternative jobs that popped up in my restless mind and to stop trying to re-invent myself. In other words, to get real. A freelance editor needs to actively look for editorial work. I had become too relaxed about scouting for new contacts, making connections, and staying in touch. This part of freelance life was not my favorite, but I knew it was necessary. I had to get serious. I did take action. I went to our local library reference department and pulled out a hard copy of Literary Market Place to begin searching for publishing companies. I spent time working through this resource and writing down potential contacts—and I made some serendipitous connections. It “just so happened” that when I contacted McGraw-Hill, they were looking for a developmental editor in life sciences. I also did work later on for W. W. Norton, Pearson Addison-Wesley, and other, smaller companies, all of which I sought out and followed up on. The following year, my income doubled. In fact, it almost tripled. The year after that, it doubled again. I’d like to say that my income stayed at that high level until I retired, but contract work is unpredictable, and the market began to change. Still, I wouldn’t have been as financially successful had I not heard that wake-up call from Suze Orman.

I said earlier that it was hard to describe the shift I felt, but I’m going to give it a try. That shift wasn’t simply getting new information and using logic to plot a rational course of action, although I did take action. Instead, it was a consciousness shift. The frame of mind, or whatever it was, that had led me into this stuck place didn’t just change; it dissolved. I think that as a result, I found open doors—doors I hadn’t looked for and hadn’t been able to look for. Opportunities suddenly appeared. Skeptics might say that those opportunities were there all along, and perhaps that’s true—but for me, they might as well have not existed until I went looking for them with my “new eyes.” |

Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed