|

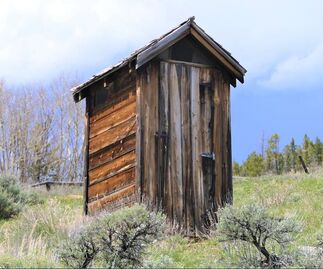

An old black-and-white photo, taken sometime around the early 1930s, shows my father as a young man, standing with his uncle outside a weathered wooden wagon. He is smiling his crooked smile and wearing, fantastically, a Spanish-style hat with a fringe of balls hanging around the wide brim. That summer, he and his uncle herded sheep on the sagebrush range near the Utah/Idaho border. As the herd wandered over the land, so did they, driving the horse-drawn wagon that had been fashioned into a house on wheels, in which they carried supplies and possibly slept during bad weather.

He was standing on the four-foot by two-foot kitchen floor—the only floor we had—sharing it with my mother, who was preparing a fried trout and canned potatoes dinner for five. She worked over a small propane range next to a foot-square sink with a foot-square counter. Mom and dad were not tall people, and that was good, because the ceiling height was only six and a half feet; but they were not really thin, either. Dad unbuttoned and slid his coat off without raising his arms, letting it drop down off his back and catching the collar as it reached his hands. He and mom then shifted places, brushing past each other in an unconscious T’ai Chi‒like move, so he could open the tiny closet door opposite the cooking area and hang his coat inside. The dining area where I sat consisted of the table in the center and tan, vinyl-covered foam seats on each side. Windows behind the seats were draped with cheap curtains of a stretchy, nubbly fabric, white with cheerful brown and yellow flowers, a wavy sewn border on the bottom in orange and brown ric-rac. The curtains always smelled of cooking, and the window screens had the dusty smell that rain sometimes has in summer. Clever storage spaces, drawers, and cupboards had been built into every available nook, and into them we stuffed all the things we needed for our summer excursions—canned and packaged foods above the sink and stove; clothing, shoes, and boots in the closet and adjacent cupboards; cooking utensils in kitchen drawers; books and games wherever they would fit; and tools and items not frequently needed in spaces under seats.

While traveling, we kids rode inside the camper, usually in the low-ceilinged part that extended above the truck cab. The space was deep enough that we could lie flat on our stomachs with our feet hanging over the table. We watched through the wide front window as the road unfolded through cool green canyons or rolled straight and monotonous over yellow-gray badlands. We held on to each other in semi-faked fear on steep mountain roads. We dozed and dreamed traveling dreams.

After our baby sister was born, our parents brought along a drawer from one of the chests of drawers at home, which my mother made into a snug bed that sat on the kitchen floor at night. The best times came in good weather, which we spent outdoors fishing or exploring during the day, and safe inside at night. Our camper was not like today’s big RVs; we could drive and camp anywhere a pickup truck could go.

In the worst times, rain or cold kept us all in the camper together. Life became like a number puzzle—one of those plastic puzzles with sliding square numbers inside. To get to anything, or to move to a different space, everything and everyone had to shift around through the one empty square, which was usually the kitchen floor. Our parents played cards, and sometimes we joined them. Hand-held electronics and the internet did not exist; we kids escaped into dozens of books and comics and drew picture stories. We had as much space to ourselves as you might in your average coffin. We breathed each other’s air, bumped into each other, went stir crazy, became frantic with my dad’s whistling under his breath. We tried not to have arguments and frequently failed. If things got too bad, someone might stomp out of the camper to sit in the truck cab, alone for a while in a smaller but more private space.

This was our paradox: free to visit remote, natural places—to float on lakes surrounded by sagebrush banks, forested hills, or redrock cliffs, to hike along streams in aspen-covered valleys—we returned every night to a one-room communal box. Cave dwellers with a carry-along cave—isn’t this the story of all nomads?

But we weren’t real nomads. It was all right for a couple of weeks to cook in a corner, try to bathe in a basin, and live on top of one another—but it wasn’t our real existence. Although we loved our summer life of fishing and roaming, three weeks at one stretch was about the most any of us could stand. This was not “vanlife” as it’s now practiced. The rest of the year we lived in the largest city in the state, in a five-bedroom house with all the conveniences, including a deep freezer for the fish. I wonder what the difference was between us and the tourists we disdained. Was it that we caught and ate trout? Or was it a false distinction, a matter only of degree? I want to remember our summers as pristine outdoor experiences—and yet I’m pretty sure that had we been backpackers or tent campers, we would have looked down on the truck-and-camper folks. Had we been ranchers, like dad’s uncle, we might have been amused, if not irritated, watching city people trudging around the country every summer “on vacation,” regardless of their choice of gear. As far as I know, one summer on the range herding sheep had been enough for my young father-to-be. He went back home after that, to work city jobs and eventually finish high school. His uncle cared for sheep all year round. For Further Exploration Nancy Weidel, Sheepwagon: Home on the Range. Glendo, WY: High Plains Press, 2001. This appears to be the definitive work on the sheepwagon and its use in the West. Click to link to press.

1 Comment

Teresa

8/20/2022 03:53:38 am

Just lovely! I thoroughly enjoyed this nostalgic look into the camper life of your youth! What a great adventure:)

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed