Over those thousands of years, any genetic differences that gave an individual an advantage in the high-altitude environment tended to be preserved and to increase in the population. This is the classic concept of natural selection. Tibetans are not the only people who live up high. The Aymara people of the Andes live at an average elevation of about 13,000 ft (4,000 meters). Humans moved into the Andes perhaps 11,000 years ago. And, the Amhara people of northwestern Ethiopia live at an average elevation of 10,663 ft (3,250 meters). Anthropologist Cynthia Beall of Case Western Reserve University has spent decades studying the physiology of high-altitude populations. Here are a few of the physiological differences among Tibetans, Andeans, and Ethiopians, based on her work and that of others: Tibetans:

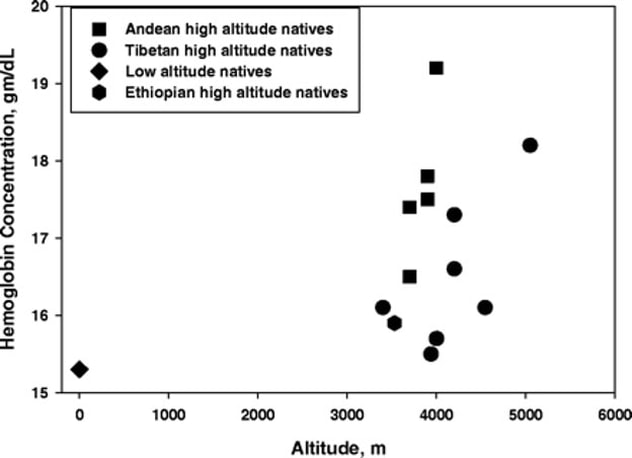

It’s puzzling how Tibetans manage to keep their physiological oxygen high enough since they don’t show increased hemoglobin or increased oxygen in hemoglobin. Basically, Tibetans tolerate having a low oxygen level in their arterial blood, and yet their tissues manage to utilize the oxygen they need. Ethiopians are another puzzle; their hemoglobin and oxygen-in-hemoglobin measurements are close to that of lowlanders, but they too are able to thrive in the highlands. The graph below illustrates hemoglobin versus altitude. Notice that low-altitude natives are shown down in the lower left corner, and that the single point for Ethiopians is between 3000 and 4000 m altitude in the lower part of the figure. Naturally, scientists are looking for clues. In the last ten years, a gene known as EPAS1 has been studied extensively. This gene plays a role in the production of erythropoietin (EPO), which controls production of red blood cells. When oxygen is low, EPAS1 transcription is turned on and stimulates EPO production. This in turn leads to increased red blood cells and thus greater oxygen availability. You may remember the Tour de France scandals of the early 2000s that involved the use of EPO by competitors as a performance enhancing drug. When lowlanders travel to high altitude, EPO increases, and this is thought to compensate for lowered oxygen availability. In Andeans living at altitude, increased EPO is a way of life. But Tibetans and Ethiopians do not show increased EPO. Because of their elevated red blood cell count, Andean natives are at risk for developing chronic mountain sickness. This ailment is a result of increased blood viscosity, which slows circulation—particularly through the lungs. These people may suffer from low oxygen in spite of high hemoglobin. Tibetans and Ethiopians, in contrast, are more likely to avoid this condition. In Tibetans, the EPAS1 gene is altered. Although it does stimulate production of EPO, it does so at a lower level. What’s more, this particular altered EPAS1 gene is found almost exclusively in Tibetans. (A small percentage of Han Chinese also carry this altered gene.) So far, Ethiopians do not show an altered EPAS1, but they do show altered versions of some other genes in the hemoglobin and red-cell pathways. Here’s another twist to the story: the altered EPAS1 of Tibetans has evidently come from a group of hominins (closely related, archaic humans) known as the Denisovans, who went extinct about 40,000 years ago. Not much is known about Denisovans because only a few fragmentary fossils have been found. DNA analysis, however, shows that they were distinct from Neanderthals and from modern humans. Interbreeding occurred among these groups on multiple occasions over thousands of years. The altered EPAS1 has no particular effect at low altitude, which may be why it has been preserved in Tibetans and Sherpa people. Adaptation to high-altitude environments has apparently taken more than one path in humans. Scientist are continuing to investigate other possibilities to explain how Tibetans, and Sherpas in particular, are able to live the high life. For further exploration

[These first four are technical articles:] Cynthia M. Beall, “Andean, Tibetan, and Ethiopian patterns of adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia.” Integrative and Comparative Biology, 46(1), February 2006. Click here. Cynthia M. Beall, “Two routes to functional adaptation: Tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), May 15, 2007. Click here. Cynthia M. Beall, Michael J. Decker, Gary M. Brittenham, et al. “An Ethiopian pattern of human adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), December 2002. Click here. Masayuki Hanaoka, Yunden Droma, Buddha Basnyat, et al. “Genetic Variants in EPAS1 Contribute to Adaptation to High-Altitude Hypoxia in Sherpas.” PLoS ONE 7(12), December 2012. Click here. [Nontechnical:] Ann Gibbons, “Tibetans Inherited High-Altitude Gene from Ancient Human.” Science, July 2, 2014. Click here. Mark Synnott, The Third Pole. New York: Dutton, Penguin Random House LLC, 2021. [This book describes the author’s journey to Everest in search of the remains of Sandy Irvine. Along the way he tells us a lot about the George Mallory expedition, about other Everest climbers, and about the Sherpas’ abilities. It was this book that introduced me to the Denisovan EPAS1 gene.]

6 Comments

Deborah Robbins

3/26/2022 01:53:58 pm

Great stuff! I wouldn’t have guessed there were multiple evolutionary adaptations to address high altitude living. Love the context provided by the photos. I have traveled to the highlands of Peru and experienced (for brief time) altitude in midteens. Yikes! Even chewing coca leaves only helped a little. Have you been to the Andes or to Tibet? How’d you get interested in this topic?

Reply

Jody

3/27/2022 06:42:24 am

I admit that I have never been to the Andes or the Himalaya. But I am fascinated (perhaps somewhat morbidly) by stories of dangerous mountaineering---or "mountainerring" as I sometimes call it.

Reply

Jody

3/27/2022 06:53:16 am

P.S. I updated this post with a new paragraph since you first read it. The added information mentions that Andeans are at greater risk for chronic mountain sickness because of their high red blood cell count.

Reply

Deborah Robbins

3/27/2022 11:30:17 am

New paragraph also surprising. My son-in-law suffers from hemochromatosis. His body produces too many red cells. As organisms, we seem precariously balanced between too much and too little for requirements.

Susana Jacobson

3/26/2022 07:31:27 pm

Very interesting how many ways there are for this to work. It says nothing about lung capacity. Doesn't that play a role as well as body conformation overall? Being a small person with a big chest and lungs would seem to help.

Reply

Jody

3/27/2022 07:30:25 am

The articles I've read don't mention lung capacity per se, but Beall's 2007 article on Tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives does discuss ventilation, which is the mechanical movement of air in and out of the lungs (basically, breathing). Tibetans have a much higher average resting ventilation (Liters of air per minute) than do Andeans---Tibetans breathe deeper and faster.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed