|

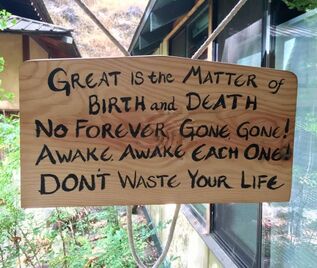

During what would be his final journey, Gautama Buddha first became ill when he and some of his disciples were staying at Beluva for the rainy season. His pain was very great, but through meditation he was able to endure it, and he made a recovery.

Masters commonly hid the inner secrets of their craft or teachings from their followers. This was termed “the master’s fist.” Gautama Buddha said that in his teachings there was no “master’s fist.” The Buddha believed that these teachings belonged to all people, without regard to caste or other distinctions. Gautama went on to say, “Ānanda, . . . I am old and wasting away with age. I have traversed life’s journey and reached the end of my time. I am already eighty. As an old cart will move only if strapped up, my body is kept going by being strapped up. It is only when . . . [I enter] into the concentration of mind that has no outward characteristics that [my] body is sound.

The word translated as “island” is dīpa. Opinions vary on the translation of this word, which can also have the meaning of “lamp” or “light.” Most evidence indicates that “island” is the intended meaning, based on how those in India depended on islands or sandbars for safety during the floods of the rainy season. Jain writings also contain dīpa in this usage. But an argument can be made for the meaning of a light or lamp, which could be used as a guide; the interpretation would then be “You should be guides unto yourselves.” Shinran, founder of the Jōdo Shin sect of Buddhism, used the word “beacon”; this word suggests a light or lighthouse marking an island, combining the two meanings in a pleasing way.

For Further Exploration:

Quotations of the Buddha are taken from Hajime Nakamura’s work Gotama Buddha: A Biography Based on the Most Reliable Texts, Vol. 2 (Tokyo: Kosei Publishing Co., 2005). The story of Buddha’s decline and death is recorded in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta (Pali version). Many translations exist, but one that is worth checking out is Last Days of the Buddha by Sister Vajira and Francis Story (Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society, 2000). Buddhist scholar Thānissaro Bhikkhu has also translated this sutra. The complete text is available online here. Mary Oliver wrote a poem about the Buddha’s death, making use of some poetic license. It’s titled “The Buddha’s Last Instruction,” and you can read it here.

1 Comment

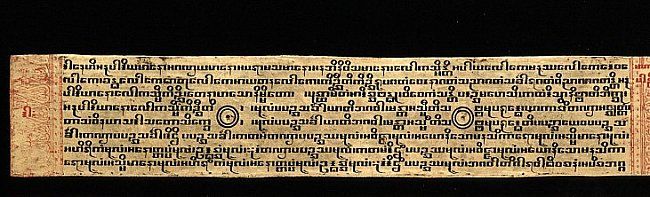

All experience is preceded by mind, All that time that the Buddha taught, forty-five years, and no one was taking notes. That’s because no written language was present in the area. It wasn’t until about 450 years after the Buddha’s death that his teachings were written down. Prior to that, the discourses were memorized and passed on orally. The Pali Canon, written in the Pali language, is the most complete Early Buddhist canon still available today. The Dhammapada is part of this canon. (Other collections are available in other languages, and some are earlier, but none is thought to be as complete.) The meanings of ancient foreign languages are subject to the interpretation of the translator. I put together the version of the stanzas at the beginning based on a number of translations into English, including that of Gil Fronsdal, Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Glenn Wallis, and Jay N. Forrest. I also checked the English meanings of some terms in the Pali Text Society’s Pali–English Dictionary. The problem with translations is that often they reflect the preferences, cultural beliefs, or level of understanding of the translator. My version naturally reflects my choice of “best words” based on my own understanding. Even well-known interpreters can put an odd slant on translations. Thomas Byrom, a scholarly translator of Buddhist works who died in 1991, comes under criticism for translating the first line as “We are what we think.” The Pali version says no such thing. (See author Bodhipaksa’s critique in the fall 2014 issue of Tricycle.) Looking deeper into meanings, “mind” could also be “heart” or “heart-mind,” because the seat of consciousness in Buddhism is in the chest (i.e., the heart) and not in the head. The word for “mind” might also be translated as “thought” or “intention.” If the mind/thought/intention is obscured, polluted, or wishing harm, then the result is suffering. If the mind/thought/intention is clear, pure, or bright, then the result is joyousness or happiness.

This idea doesn’t mean you change your outlook in order to change the world. The world is how it is, regardless. It also doesn’t mean that you pretend you aren’t angry when you are, or that you adopt a false generosity to make yourself feel better. The important thing from a Buddhist point of view is to shift your own perception, understanding, and intentions.

Gautama Buddha was eighty, and he was feeling his age—he compared his body to an old cart that will move only if held together with straps. But through entering into “the concentration of mind that has no outward characteristics,” he could remain comfortable. He had decided some months earlier, at Vulture Peak, to travel back to his home in Kapilavastu, where he spent the first twenty-nine years of his life. This was a journey of some 200 miles, on foot. Now he was in the city of Vaiśālī (Vesālī), a place he had stayed often during his travels.

The next morning, Gautama rose early to beg for alms. After he had eaten, he “turned his body to the right and [while turning,] looked around in every direction with his elephant’s gaze.” He said to Ānanda, “Ānanda, this is the last time I will look upon Vaiśālī.” Gautama is saying goodbye to places he has appreciated during his life. He feels a nostalgia that many people feel as the end of life approaches. Some scholars are critical of this passage, stating that these are not the sentiments of an enlightened being. (One wonders how they would know.) Their objection makes sense only if being free of emotion, that is, feeling nothing, is a Buddhist value. I think this is an error. Buddhists are not striving to become robots; emotions are a fundamental part of who we are. Gautama was a human being with human feelings—but he was not bound by habitual patterns of reaction.†

*Quotations and descriptions are taken from Gotama Buddha: A Biography Based on the Most Reliable Texts, vols. 1 & 2, by Hajime Nakamura (Gaynor Sekimori, transl.) (Kosei Publishing Co., 2005). This is a scholarly work that uses a variety of sources and Buddhist texts. It’s currently out of print.

†For one discussion of emotions in Buddhism, see “Buddhist Insights for Accepting and Respecting Our Emotions,” by Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, Huffpost, 06/04/2010. Click here.)

At the time I posted about this, I wondered whether daily life would have a different pace if we paid attention only to hours, rather than to minutes, let alone seconds. The development of mechanical clocks allowed tracking of time during both day and night, and on cloudy days—a definite advantage over the sundial.

Much of my work life was run by deadlines. That’s not true now, but sometimes I still tend to behave and feel as though it is. I get over-invested in punctuality and making sure things are done “on time.” I almost never have a set schedule these days; my day planner is largely empty space. But that old drive lingers on. The drive is the problem, not setting a time or meeting an appointment. It’s about how I approach these set points. In 1970, Gestalt therapist Barry Stevens published a book titled Don't Push the River (It Flows by Itself). The title was arguably the best part. I have spent so much time pushing the river.

Either way, I still got to the hall. When I moved deliberately but without rushing, staying in the flow, I found my mind was already more at rest when meditation began.

Time passes, whether precisely measured or not. Sometimes we do need to work quickly or move swiftly—but we gain nothing when we translate that into feeling pressured, pushed, anxious, or rushed because of old habits.

If you are someone who grew up with a Western mindset, then you might likely strive to determine once and for all what is right and what is wrong, so that you can be in the right and can relax. You know the result of this quest: opinions differ. We don’t have to look far to see how this dichotomy between good and bad works on us. Social media and news media play us—and prey on us—by presenting events in a hyped-up, dramatic light. It’s easy to be agitated and upset constantly from viewing media. We just want it to stop—“it” being whatever the currently designated evil is. Things that have nothing to do with me are made my business. I am invited to be outraged by injustice, broken by tragedy, frightened by the actions of others, even terrified by the weather forecast—until the ad break, where I’m assured that with the right beer, a better cellphone, a new car, or a doctor’s prescription, I can be okay again. Chögyam Trungpa is using the light-and-dark analogy to attempt to explain a difference in perception—but it’s easy to misinterpret what he means. He does not mean that light and dark are the same thing. Everything does not exist in a monochromatic gray fog where anything goes. Bad acts and good acts do happen, and we can discern the difference. He also does not mean that light and dark never change. Looked at from high Earth orbit, we see that at any given moment, half the world is in darkness and half is in the light, but each area is continuously moving from one to the other. (Does this sound like Taoism? There’s a reason for that. Chinese Chan Buddhism, the originating tradition of Japanese Zen Buddhism, incorporates much of the older Taoist philosophy.) The Buddha-Tao mindset invites us to view events in a dispassionate way: suspending judgment, preference, and conditioning, if only for a moment. By doing this, we can see what is happening without a knee-jerk reaction based on prior emotions, favorite ideas, childhood conditioning and beliefs—or on being manipulated by a party line or a media ad campaign.

|

Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed