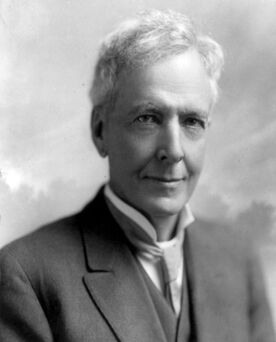

“Burbank was a plant mystic who created new plants with little more than his imagination, his pollinating abilities, and his skill for selection.” —Jules Janick Luther Burbank was born in 1849 in Lancaster, Massachusetts, to Samuel Burbank and his third wife, Olive Burpee Ross. The thirteenth of his father’s fifteen children, Luther was drawn to plants and flowers from an early age. A flower could give him greater pleasure than any other kind of toy, according to biographer Henry Smith Williams.

George Harrison Shull, a biologist who worked with corn, reviewed Burbank’s work in the early 1900s and determined that Burbank’s processes were “more art than science.” Luther Burbank’s role in the creation and development of the Russet Burbank potato was his first great success. In his early 20s, he read Charles Darwin’s book The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication and was impressed by the ideas. He also purchased a 17-acre farm where he planned to grow vegetables and also to “accelerate evolutionary changes,” according to biographer Jules Janick.

Cultivated potatoes depend more on their tubers than on flowers and fruit for reproduction, and the appearance of an actual seedpod is relatively rare. Inside this single seedpod were twenty-three seeds. Burbank planted all twenty-three to see what would come of them. One plant produced large, excellent tubers that tasted good and could be stored for a long time. This was the “Burbank” potato.

Burbank had a connection with plants that went beyond intellectual curiosity. He did have a method for producing his hybrids, but I think that the plants responded to his positive attention and connection as well. I’m not saying that plants have emotions or animal-like consciousness; I am no fan of anthropomorphizing. Plants do not have brains or nervous systems in the animal sense. Plants do respond to stimuli from their environment, however, and part of those stimuli may come from organisms around them, including humans. Just because we have no explanation at this moment doesn’t mean the idea is impossible. In any case, Burbank loved plants, and he certainly reaped rewards from his wizard-like work with them. For further exploration

Michael Pollan has written a fairly well-balanced article about the topic of plant “intelligence”—it appeared in the December 23 & 30, 2013, issue of The New Yorker. You can read it here. Jules Janick, “Luther Burbank: Plant Breeding Artist, Horticulturist, and Legend.” HortScience Vol. 50(2), February 2015. American Society for Horticultural Science. You can read and download a PDF here. Henry Smith Williams, Luther Burbank, His Life and Work. New York: Hearst’s International Library Co. (1915). Available in ebook/Kindle form from HardPress, Miami, FL (2017).

1 Comment

Teresa

1/28/2022 05:10:12 am

Interesting read!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed